October 6, 2000/May 18, 2006

by Phoenix

Foreword

1. A Reintroduction to Capitalism

2. Value, Capital, and Currency

3. Exchange and Markets

4. Property and Arbitration

5. Environments and Resources

6. Monopolies

7. Economic Fascism

8. Symptoms of Controlled Economies

9. The Minimal State and Fascism

10. Charities

11. Corporations and Corporatism

12. Commercialism

13. The Economic Zero-Sum Fallacy

14. Nature and Promethean Capitalism

Foreword

This series of essays explores economic and financial issues from a Promethean perspective. In part, they expand on the brief economic discussions found within The Promethean Trilogy. They also explore the free economy of a Promethean society in a more complete way. Additionally, these essays examine a number of debates surrounding economics: debates about capitalism (according to different meanings of the word), freedom of exchange and free markets, making money, control of economic activity, economic exploitation, ownership, and more. Taken as a group, these essays will give the reader a more complete understanding of what economic system is pursued by the Promethean movement, and why… Promethean capitalism, concisely described as true free-market capitalism, fully-consensual free enterprise and exchange for every individual.

This is not a collection of essays written foremost for the purpose of supporting ‘capitalism’ by any meaning, or any economic system. Rather, these are essays composed to contribute to Prometheanism, the philosophy of the Promethean movement, which places the integrated personal strength and advancement of individual human life first. As the economic component of that approach, these essays happen to endorse a certain sense of the word capitalism, because Promethean capitalism is necessary and beneficial to that purpose. No system should be the basic goal and the measure in the economic realm, or any other; impact on human life of each person and especially one’s own life (always our window to lives of others) must be considered. Always attention must be given to the fulfillment, and advantages, and progress to the fullest potential of our lives. The system of capitalist economics as I will discuss it is favored in part because it is not a system which is planned and controlled, except at an individual level; it is as organically decentralized as natural life itself.

Promethean capitalism does not bear resemblance to anything in common practice today. It is however built upon the uncommon work of many people, and the logical conclusion to the tradition of economic freedom. Although those who have contributed to this tradition over the centuries are too numerous to acknowledge here, I wish to begin this series by crediting them, especially those thinkers whose work implies the radical freedom which is endorsed and sought here in the name of Prometheanism.

1. A Reintroduction to Capitalism

Before we can address the kind of capitalism which is desirable, and before we can address the debates surrounding capitalism, its successes and its failures, we must first ask: what is capitalism?

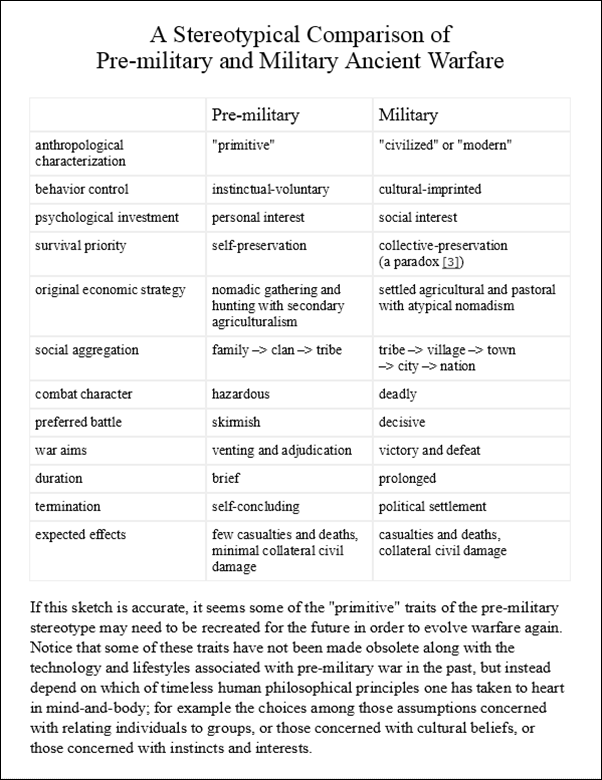

There have been very many different traditions of capitalism. There is the concept of free enterprise. There is free trade and exchange. There is the principle of private ownership. There is liberalism in the traditional sense. Classical liberalism attempts to reconcile its tenets of predominant ‘individual rights,’ especially the right of property, with limited constitutional government which exists to guarantee those rights, claiming that this arrangement is a free market. The tradition of laissez-faire capitalism is a loose idea based on the principle laissez faire, to let [things] alone. There are various schools of economics with their own developments on the theme of capitalism, such as the Chicago school economists, or the Austrian school economists. Recently, there has also been the idea of capitalism as a moral system according to Objectivism and its derivative movements. And then there is capitalism simply as making money, and a capitalist simply as one who makes money.

And how is the word capitalism generally understood today?

A dictionary will define the word this way, or similarly:

1. An economic system, marked by a free market and open competition, in which goods are produced for profit, labor is performed for wages, and the means of production and distribution are privately owned.

2. A political or social system regarded as being based on capitalism.

(source: American Heritage)

Most of the first definition above is extraneous, or misleading. The system commonly regarded as capitalism today does not have a free market (unhindered, voluntary exchange) or open competition. Some labor is not performed for wages (for example, an approximate average of one-third of labor is the U.S. is ‘owed’ to the state), and a large proportion of the means of production and distribution are not privately owned, they are state-owned.

And, if capitalism is just “an economic system” among other possible systems, why choose it over others? If it is characterized by producing goods for profit and performing labor for wages, why not experiment with other possibilities such as labor performed without wages, or goods produced without profit? Why not tinker with a market; why not experiment with partially-free markets or less-than-open competition? And why not have all or some of “the means of production and distribution” outside of private hands?

This has all been done and continues to be done, and it has all failed in terms of beneficial impact on human lives. This experimentation has led to the condition of so-called ‘capitalism’ today. There has been a failure to understand the essence of the issue; there has been a failure to understand capitalism. There has been a failure to understand what is at stake, and there has been a failure to understand what is really of value.

The second definition more accurately describes what is called capitalism by most people today, and gets at the heart of a problem: what most people call capitalism as a sociopolitical system is merely something regarded as such, rather than a sociopolitical circumstance which follows from the economics of what capitalism really is, at its root — or what it should be.

The dictionary definitions I quoted above, as well as most economic, social, and political discourse on capitalism, is removed, theoretical, cold, impersonal, even antiseptic — everything but realistic and human and immediate. But the real point of it all is immediate, and it is human, and it is personal.

What distinguishes capitalism is first of all simply an absence of something, and the consequences which follow. That something is compulsion in matters of economics — matters of trade and ownership. Capitalism is founded on choice for each person over themselves and their own affairs, as well as their interactions with others, rather than considering domination and interference to be acceptable.

Capitalism as a tradition is essentially individual economic freedom, a tradition with ancient roots around the world. That this has been diluted, and at times discarded, does not change that capitalism represents the economic aspect of a wider regard for individual freedom, which has also found many other expressions. ‘Capitalism’ today is not capitalism as a fulfillment of this theory.

I identify certain elements as essential to the tradition of capitalism, all connected and inseparable dimensions of what we might call economic individualism:

1. Individual private ownership of person, and whatever material possessions can be recognized to belong, rather than the rights of other people (or group rights) to individual person and property.

2. Voluntary labor and effort by each person, i.e. the absence of compulsory labor (also known as slavery).

3. Voluntary exchange, whether through barter or the use of an agreeable medium of exchange.

4. Free trade across artificial lines which divide individuals into groups. The advantages of free exchange between people imply the unimportance of division, and the erosion of official borders as well as collective divisions which exist only in belief, such as religion, race, ethnicity, etc.

Capitalism as a tradition of freedom emphasizes the individual over the collective group, prefers free and voluntary interaction to compulsory, and is tolerant of diversity among individuals and in practical terms, favors and rewards it (especially specialization, but also the ability to adapt and draw upon multiple capacities).

The logical fulfillment of this would be the most radical of all possible elimination of restriction on individual economic freedom. It would imply the most radically individual understanding of economic identity. It would also foster the greatest possible individual diversity.

Given the essence of capitalism: the logical destination of the tradition of capitalism is real free-market capitalism, a stateless free market based on individual rather than group identity, on individuality, and on individual freedom.

Thus in Promethean Capitalism I have chosen the phrase “Promethean capitalism” to describe a radical, true free market of individuals, which I believe is the economic circumstance most conducive to individual accomplishment and improvement.

Some will still wonder: why use the word ‘capitalism’ if capitalism is now considered to be something other than Promethean capitalism — why use the phrase “Promethean Capitalism?” Why not abandon ‘capitalism’ to what is today a perversion of individual freedom, even if I am right about the unfulfilled ‘soul’ of capitalism as it should be?

In every great tradition, every tradition founded on something essential, important, and beneficial, there will evolve the complexity of distortion and obfuscation as that tradition evolves (more so if the potential of such a tradition has never been fully pursued and realized). But that does not condemn the essence of such a tradition, or prevent us from defending that essence from its corruption and ultimately returning it to its worthiest meaning. We should preserve and continue what has been great and beneficial, and object to what has not. We should continue the tradition of what has been contributed toward personal freedom in the name of capitalism — not abandon the name of capitalism to what really belongs to authoritarianism, or to exploitation, or to the impersonal, or to the half-realized life. Capitalism belongs to us.

2. Value, Capital, and Currency

Many people who do not care about money as a main goal believe that economics of any sort has little to do with them. Or, they feel that economics does not describe what they care about at all. Some rarely think about economic concerns in the first place; money occurs to them as an issue only when it becomes an obvious concern, or in some other way passes right in front of their face. Exceedingly prevalent, and dangerous, is the idea that they should not care about economic freedom and do not need to, since they have no obsession with making lots of money. As ‘little people’ in economic terms, many expect advantages from redistribution of wealth taxed from those who make the most money, or have the most money.

And most economists, who naturally care about money very much, are generally not able to identify with these other perspectives enough to effectively dissuade people from those beliefs, even free-market economists.

One mistake has been to limit the discussion of free enterprise to the financial and the physical. Capitalism would seem to be about financial capital — the physical manifestations of it, currency and resources and possessions which convert to currency, and the exchange of this capital. This is only the roughest and most closed understanding of capitalism. Unfortunately it is a popular one, especially among rulers, and one prevalent among critics of free markets.

There is much more, or can be much more, to capitalism than money. To understand how and why, it is necessary to reintroduce ourselves to money.

Money or currency is a medium of exchange which is supposed to represent value. Governments now manufacture money by printing or coining official currency. Of course, to get us to care about official currency in the first place, governments bridged from precious metal. Computerized credit now represents paper money and coinage. Paper money originally represented gold when there was a gold standard and coins were precious metal. Long before this, gold, and originally silver became standards because they were rare and durable, malleable into coins, and had useful value on their own as commodities. Far from being an original product of central government, money was a commodity adopted for exchange. The most marketable commodity tends to become the standard known as money in a given context or culture. In various places and times, people have used cowry shells, beads, barley, lead, copper, or clay tokens, sometimes different clay tokens for different commodities. And originally, there was no symbolic money — there was only the inefficiency of direct bartering.

For streamlining transactions, representations of money may be used which are worthless in themselves without solid reference to the commodity which has been accepted as money, until that representation is accepted as a commodity of exchange in itself. The electronic credit which represents cash today is worthless without that connection. However, paper money no longer requires a direct link to gold, because there is a belief in its validity as a standard. The evolution of that belief has had much to do with the intrusion of government into money and exchange.

Besides making trade and exchange easier, the invention of money also made taxation easier. As soon as a standard naturally evolved as a more efficient means of exchange than barter, the taxation also became more efficient. Instead of a percentage of the harvest or the herd, rulers could appropriate money. For some centuries, decentralized and unofficial money actually existed side-by-side with government, and official taxation.

Then, although money had begun as an evolving standard to represent value (whatever worked well), rulers discovered that by centralizing money, issuing official, enforced, and regulated currency, they gained an unprecedented level of control over exchanges within society. Through this monopoly over value when it is exchanged, governments acquired the means to interfere in the exchange of value, to appropriate value, and to simulate the original creation of value by creating for itself more of the means of exchange. Even more far-reaching was the interference of this ‘objective value’ in the definition of value itself. Official money has become official value.

Control of money has become control of value, thereby culturally fostering a falsely objective value. Public policy-makers always care about centrally-minted legal money (printing it does fuel governments, after all). We often get the feeling that we are all supposed to care about it, even if we are not disposed to a great interest in trading or business, even if money would serve us best as a means, and not a standard of value. In the hands of a central authority, money has become a prime influence of social control, in addition to being a useful tool.

Governments now manufacture money by printing or coining it. But governments produce what stands for value; they do not produce value in itself. Governments try to set objective monetary values and manipulate them, but all conceptions of value are subjective, as the products of different individual minds. The idea of objective value is artificial. It depends on external control of what we believe and what we use. That is why in a Promethean society, a free society, there must be no official currency. Decentralization of currency is the foundation of a truly free economy, in a truly free society. Any standard which can be agreed upon as a means of exchange for any given transaction, is a valid one. Who can say what shared standard or standards will be found when there is no interference with choices? Perhaps more than one kind of currency will work better than just one. Perhaps gold will again be standard, except with multiple independent standards for its verification. We do not know, because force has been used for thousands of years now to control a monopoly on currency.

A decentralized, individual understanding of capital is just as important. Anything which can be exchanged, or converted to a form which can be exchanged, can be considered capital. But so can anything which has value for one individual, yet others would not accept in any exchange, at least in its current form. Plenty of experiences, knowledge, beliefs, and other thoughts have value only to the person who possesses them. In intangible ways, perhaps these contribute to capital others would care about — or perhaps not. However, to the individual who does care, they do have value. Now, externally or ‘objectively’ that is not monetary value. But that is not necessarily important to a person, nor should it be, if their idea of profit is something else in a given context. An individual understanding and assignation of value allows for this. This is a major reason why an individually free economy may be said to be most essential to those whose chief interests are not financial; only when the identity of value and capital are freely determined individually, and this freedom is recognized, are other personal interests besides the financial definitely allowed to be a factor to the extent that they matter to a person, such as artistic creativity, family, privacy, abstract thinking, recreation, etc.

The point of Promethean capitalism is the freedom to define one’s goals subjectively, as one desires, and the freedom to pursue them.

Capitalism is for everyone.

3. Exchange and Markets

An economy is the financial dimension of a culture, indivisible from all the complexities of a culture, and inseparable from the origin of culture in the interactions and exchanges between individuals. Although the words economy and market typically relate to exchanges which relate to money and finance in an apparent way, these are subsets of a larger complex web of all human cultural exchange.

An economy begins in its essential form with the exchange of one thing for another between two individuals. What is exchanged might be an object, a service, an action, loyalty, an idea, knowledge, information, words, or even nothing appreciable. Anything can be exchanged which can be assigned subjective value (even if that value is understood to be nil), a value which may be conceived differently by the two individuals. Typically, what is exchanged is something desired by an individual who receives it.

In practice, the economy of a society (a society being nothing other than a group of interacting individuals) is composed of many, many such exchanges in a complex web so vast and interconnected it can be described only with difficulty, and often predicted with much less certainty than the weather; both of these are complex systems in mathematical terms. A market in economic terms is the totality of this web of exchange, which invariably gains its larger character from the qualities of individual exchanges, and the subjective conceptions of value in each case, since it is composed of nothing else. Some of these exchanges will involve groups of individuals; in this case the dynamics between these individuals as well as their individual conceptions (which of course may themselves be of infinite variety) must be considered. This general categorization could describe every possible exchange, economy, and market.

Marveling at the sheer complexity of any large market, we begin to see why ‘market planning,’ actually an attempt to control markets centrally, does not fare well. Not only are there trillions upon trillions of individual exchanges (or even many more) contributing to larger ‘market forces,’ some of these are not even measurable, many of them do not use money at all, and all of them (despite the present existence of official currency as a standard of value) are based on individual subjectivity at some level. A market can only be planned if the scope of organic human interaction can be planned — obviously quite impossible. To regulate and plan such a thing is beyond any human being’s comprehension; it is somewhat like planning a universe. Chaos mathematicians have a term for this, a complex system — something so complicated and intricate that any estimation of order can only fail as a model — a system that cannot be systematized. Most known complex systems are built from simple basics to be complex upon the multiplied interaction of the basics. But markets are complex upon complex, because the most basic exchange results from the inherent complexities of at least two human minds. The complexity of a stock exchange itself is considerable, yet the immediacies of this little corner of a market are a tiny subset of all the factors involved. The internet includes incomprehensible complexity, yet all electronic exchanges of ideas and information are merely a minor part of all cultural and financial exchange in the worldwide market.

Although exchanges which do not involve a recognized form of currency are rarely allowed to be centrally controlled and regulated to the extent that financial exchanges are, control over financial exchanges are accepted, even where people do realize that other exchanges should not be regulated and controlled. Few people would accept central control over the exchange of words, thoughts, or favors — but taxation and regulation are accepted as soon as a medium of exchange is introduced. This is foolish, because one kind of control very often leads to another.

When an exchange is voluntary — which occurs when the two things exchanged are (subjectively) agreed by both parties to be of equal value, or when inequality is recognized by one or both parties, yet judged as an acceptable condition of the exchange by both — then that exchange is a free exchange, the basic element of a free economy. Note that gift-giving from presents to charity is included in this definition as an acceptable unequal exchange of something for nothing, perhaps derived from a sense of obligation, or a desire to inspire one. Or, gift-giving can be an exchange for nothing immediately substantive, but providing a sense of well-being for the giver which is worth something too — maybe much more than the gift itself.

As long as every exchange within a market which is not voluntary is aberrant (as in the case of theft), and every group acting as a party of exchange is based on entirely voluntary association, that market is a free market. Notice that provision is made here for the case of theft and other acts of violation and exploitation as aberrations, since otherwise no free market could exist on a large scale. But notice something else:

1) Government acting as a representative of a people is not a voluntary association, yet it represents a party of exchange.

2) Taxation, seizure, duty, and other ‘exchanges’ involving government are not considered to be equal by both parties, and certainly they are usually not agreeable.

3) These non-voluntary exchanges are not aberrant, but widespread, comprising a significant proportion of all exchanges within societies incorporating government — which is to say virtually every territorial society in existence.

For an economy to be a free market, it cannot be composed of exchanges which are not voluntary, so it cannot involve government. Even a laissez-faire, minimized state still would not possess a free market. No society founded on the principles of collectivism and compulsive central authority has a free market, or a free culture, for that matter. Unhindered by government and founded on individualism, a Promethean society can have a real free market and a free culture; a Promethean society can benefit from Promethean capitalism.

What are the advantages of this Promethean capitalism? Aside from the innate appeal of personal freedom, the most obvious potential advantage from a given voluntary exchange is this: since value based on need or desire is subjective to each individual, advantage may be derived by each party to an exchange without exploitation. Because individuals have different capital to trade and different desires, exchanges can reward both sides. Both can be self-interested, both can win. (Of course both do not always win — not if a choice is foolishly or ignorantly made, or if deceit is involved. But these are not problems which concern only voluntary exchanges.) Both individuals who trade can profit according to their own definition of success, however this is defined. This most immediate advantage is also the most important, for each person. But on the large scale of a market, there are additional advantages which accumulate for many individuals.

One point to stress is that capitalism depends on private, personal capital, but not necessarily only private profit; any number of people may benefit incidentally or indirectly from an exchange. And they commonly do, even when there are limitations and restrictions placed on free exchange, in a market which is not free. Imagine how much more is possible in Promethean capitalism.

The achievements of any individual can be exchanged as capital. Much of that capital is mental capital, which can circulate and become useful to many people. Ideas, knowledge, and methodology propagate expansively as a side effect of individual exchanges and individual profits. The subjective profits from each exchange spread from one exchange to another. Improved methods of production coupled with competition lower the prices of goods, even for those who have not invented those methods — yet reward the inventors. Scientific advances pass to those who have no knowledge of science — yet reward the scientists. Through the web of market exchange, wages for physical labor become intellectual education or medical care, rewarding the physical laborer, the teacher, and the doctor along the way, with very little waste due to friction, thanks to choice and competition. Improvements spread, relative prices go down, and relative wages go up. As millions or billions of people conduct trillions upon trillions of interconnected exchanges over time, productivity, capital, wealth, achievement, and individual benefit which is possible and realized can build upon itself at a fantastic rate. At the same time as there is enormous progress and advancement, everywhere, time and effort can be saved and devoted toward what matters to each person. Quite simply, whatever is valuable to you is more likely to become possible through both your own efforts, and through the pursuits of other people seeking their own kind of advantage, in their own way.

4. Property and Arbitration

Even before exchange is possible, there must be an understanding of property, a sense in which what will be exchanged belongs to the person who will exchange it. Otherwise, one would simply take things rather than offering an exchange of mutual benefit. For a functional market and a functional society, it is easy to see that understandings of personal, or shared property, had to evolve.

The idea of the private ownership of valuable capital is a great contribution to economic life. It is a natural extension of the idea of belonging — what a person does, creates, or is associated with most directly, belongs to them. This is ownership, or property, by creation. Naturally, in this sense capital inherently belongs to someone. This meaning of ownership is not transferable; whether a painter still has a painting or has given it away, it remains his by the deed of creation. And in the same sense, this writing will always remain mine most directly. Almost certainly, this property-by-creation would have been the first understanding of belonging and ownership, the association of the deed with the one who has accomplished it.

But, in order to exchange the physical property which is created or maintained by people, more is required. There needs to be an understanding of property which can be transferred from one owner to another, used or exchanged again according to the desire of the owner. This sort of property is beneficial and useful so long as it is an understanding resulting from voluntary exchanges, or from the original effort invested in its creation (with goods, for example) or development (in the case of land) before it has been exchanged. An understanding of exchangeable private property, connected to accomplishment and use, is essential for mutual benefit within a market.

However, over history the concurrent development of an understanding of private property with the development of law has not produced a consistently desirable result. The law as the codification of official, governmental opinion asserts a monopoly over the definition of belonging, a monopoly which is ultimately supported by force.

The assigned role of defining and guaranteeing property, coupled with the monopoly on force which can take it away, has ensured a conflict of interest within the government. For example, the U.S. government has come to own almost one-third of U.S. land through eminent domain, environmental decrees, and asset forfeiture, much of it without compensation. This is the eventual result of mastery over private property, characterized as early as 1795 by the attitude of the U.S. Supreme Court: “the despotic power, as it has been aptly called by some writers, of taking private property, when state necessity requires it, exists in every government… government could not subsist without it.”

An extreme example of this conflict of interest occurred in the western United States in the 19th century, after the Civil War. During this time a coalition of government-subsidized railroads, and politicians, many of whom were bribed or had financial interests in the railroads, willfully displaced, starved out, and murdered Native American settlers of western lands so that the railroads might expand through the country. Vast tracts of land were provided to these corporations through official land grants, in contradiction to the established ownership of the same land by native Americans, who were not considered official citizens with legal property rights. The army was employed to support the planned, legal theft of this land through organized genocide, which General Sherman would approvingly label as “the final solution to the Indian problem” in 1867. Clearly the land belonged to the Indians, and clearly they were people — but they were not full people officially, and therefore had no official rights to land, or any property. Neither property nor profit were to blame for what followed from the exploitation of law and governmental force, and the system which made it so easy.

In the past, when the most significant private property was physical, the protection of property under law served people well for the most part. Property such as land is relatively easy to record officially. The intervention of law to protect it generally benefits people, provided of course that recognized property has not been obtained involuntarily, through influence with government as the guarantor and arbitrator of property, as in the example of the railroads. But even when property law works without corruption, there also comes an unyielding artificial definition of property. If the law recognizes property, it is owned. If not, law as the recognized social confirmation of property in the eyes of others, discounts ownership. At best, law only follows the custom of property as it is already recognized, as with the American Homestead Act of 1862, which granted legal title to ‘squatters’ who had already been farming land for at least five years. Where it fails to recognize this easily enough, squatters remain squatters rather than owners, and businesses remain black-market, unable to acquire the legitimacy necessary to succeed in a society with law. The failure of official property to follow custom is an enormous barrier to prosperity in developing countries.

And law is a labyrinthine accumulation of tradition, legislation, and precedent dating far back into history. It is rarely relieved of any bulk or complexity; it is regularly enlarged. Property law today retains remnants of conceptions of property from long ago. Like any protected bureaucracy, legal administration is not efficient or responsive at reflecting present day. Even aside from the problem of making mistakes (which is always more common in a bloated bureaucracy), this sometimes means that legal property is far removed from an understanding of property as it is currently created, developed, maintained, used, and exchanged.

The problems with legal definition and enforcement of property are largely inseparable from the realities of law as a province of government. Government evolved in large part in order to defend and administer territorial divisions, and was designed over millennia according to the job. A mentality was thereby developed and acquired which still exists today. Among other things, this mentality values the maintenance of an enduring, regimented order, and recognizes static relationships where none exist. The bureaucratic, ruling tradition still defends what exists with a clannish singularity of purpose, distrusting change just as ancient rulers distrusted strangers in their fiefs. Governments assume the exclusive right to force and even deceive in order to defend their turf. This mentality was not developed for commercial application, and sits at odds with what is necessary for exchange. Production and trade require and seek openness.

Turf boundaries and borders, whether physical or mental, get in the way when valuable property means more than land. Government really outlived its usefulness as an arbiter of ownership as soon as wealth began to mean something more than agricultural production. Land can be effectively recorded as fixed property even when the origin of its ownership comes from tradition and use. But other kinds of capital and property are more difficult, especially when they are not objects. Property has now outgrown law.

The most telling example of this is the current debate over intellectual property. Law still approaches ownership of ideas in the very same way it approaches the ownership of physical possessions. Rules and certain exceptions are made for the ownership of intellectual creations through patents and copyrights and trademarks, they become precedent, and they are doggedly enforced. But knowledge and ideas are mental capital, they are not physical capital. They can be copied and exchanged freely by word of mouth or through modern technology. People are making use of this ability even as the law forbids it, and is powerless to stop it. Infringing on a trademark or copying music electronically may be illegal, but it is not theft. What people have discovered in practice is that they can profit from the exchange of the intellectual capital they already have in their mind, or recorded on media. Intellectual property still has its owners by creation, and it has its owners who possess it and use it. It just does not exist neatly as the sort of fixed property that government is used to defining.

One criticism of unenforced intellectual property is that those who invest in the development of a profitable concept will not be ensured a reward commensurate with their investment. It is imagined that the writer of a novel who makes a deal with one publisher will immediately find copies of that novel on the market, published without compensation for the author. It is imagined that an inventor without the protection of a patent will find his invention copied by large companies and his development efforts wasted. It is imagined that companies will find their competitors instantly copying their products. This is a distortion. Not only is it possible for agreements over the ownership of concepts to be made voluntarily, respectability might depend on it within an industry. Even now with enforced intellectual property, this is more powerful than legal enforcement. What would authors think of a publisher who did not respect authorship? In a free marketplace, what would people within industries think of companies who showed no recognition for inventors? We should note that the major modern examples of companies copying the work of others directly are corporate coalitions between government and business which can depend on official support to maintain their position, the large corporations of China and Japan for example. These are not subject to the full tests of marketplace reputation.

An evolution to intellectual property by voluntary recognition only will make for a more competitive marketplace. But there is nothing little undesirable about this, and there is much which is desirable. Rising through intellectual advantages may take great ability, but so much the better. In such a market, the most driven and able people will be competing hotly to perform better for customers at every stage, from concept development, to production, to delivery. This will reward greater adaptability and talent, greater organizational skills, greater daring. It will open the market to smaller competitors challenging established companies. It will help to develop business and exchange to reward those who take action and pursue innovation rather than those who just maintain a position. This is what capitalism should be.

The creators of many kinds of intellectual property are already discovering that they can profit in this fluid property environment along with customers, they just need to find new methods and new models which are different from the standards based on static, fixed property. Enforcing direct sales on every single use of an idea is unrealistic. Publishers discovered this when copiers were introduced. Today voluntary contributions by institutions with copiers, such as universities, replace any lost profit. The model of contributions for future work is one example of another model. Another is counting on the desire of people to voluntarily support what they value, counting on the infrequency of unmitigated thievery, an approach which has already worked with software, music, and other media.

Since a Promethean society does not have territorial government, those who live in it must replace the official, legal guarantee of property, with the arbitration of property disputes. They must find and adopt standards for the recognition of property, and independent agencies without the conflicts of interest that officials often have. But it is not necessary to have a detailed, specific, centralized plan for the notation and guarantee of every kind of property, before the foundation of a Promethean society. That would be law-code thinking again, suitable for centralized planning but not for an organic, free society. There may not be one best way of accounting for property by an independent agency. What is necessary is just the organization of some initial standards, which can be replaced or change over time under the combined scrutiny of the independent choices of a market.

Some standards would have to be used by a third-party arbitrator to determine ownership, in cases of dispute. Usually this would be possession, but not in the case of possession of property which has been stolen, obviously. Evidence could be submitted for each side, just as it is in court today. Ownership is already well understood by expectation, in most circumstances. The choices required in a market will find solutions to the specific questions, such as access to resources, and when intellectual ownership might have to be respected. Practice will find what works in practice, and independent, private arbitration will respond far more readily than law.

Legal standards need not be what works, or what makes any sense — but if a law exists, it is defended for the sake of inertial hegemony (assuming an absence of the corruption which is actually quite common). As opposed to legal standards for property, market forces do tend to find solutions which work. Fixed property in the context of media does not work. Property based on use does. However, fixed property in the context of land is a defensible standard. There also may be adoptions of use-based and fixed standards for the same types of property which are more or less applicable within different contexts. Only a decentralized market will find these and respond.

If private arbitration of property seems implausible, it is worth considering that commercial law did not evolve from a ruling tradition, quite the opposite. It was adopted into public law from private arbitration which was invented independently out of desire and need. In Europe, feudal law was intimate with rank, and incapable of the ‘radical’ assumption of individual equitability in the arbitration of disputes, an assumption which was becoming necessary for commerce. Merchants established their own courts of arbitration based on expectation and the accumulation of precedent, the custom of merchants, beginning in 12th century Italy. This “law merchant” system was the first administration of disputes in Europe which was capable of fairly deciding commercial issues, and was the first one which might have been able to recognize claimants to property (including land) on an equitable basis. Considering that this came from private ingenuity rather than territorial government, does it really require much imagination to conceive of independent arbitration of the ownership of property, as well as contract dispute over the exchange of property?

5. Environments and Resources

A paradoxical objection to ‘capitalism’ as it exists today is that it brings too much progress and production, which harms natural environments as resources are consumed and wastes are created. The remedy, we are often told, is to ‘put the brakes’ on unhindered profit and production by empowering government with a mandate to interfere whenever it is deemed necessary by the bureaucratic officials charged with oversight. But progress is not the enemy of people or of environments. It is quite important to have unhindered economic progress if the environmental problems which always arise as civilization develops are to be solved. The expansion and change that are quite naturally a part of human civilization mean that our interaction with land, air, water, natural resources, environments, flora and fauna, and ecosystems must always be reconciled with the constant reinterpretation of financial, personal, scientific, medicinal, technological, and other interests. So it has always been, and so it will always be. There is no avoiding the reality that problems will arise and require answers. But these answers depend on achievement and development rather than bureaucratic control, especially scientific and technological development, which is the product of progress within a free market. Governmental interference to slow down economic progress will also slow down the means for finding solutions: individual accomplishment.

That is not to say that in the stateless free market of Promethean capitalism, people must never express displeasure with what is done with the resources of business and industry under its private and personal ownership, simply because of the general interest of progress. In Promethean capitalism, private ownership of land and resources by an individual or voluntary group does mean that it belongs to them for their use as they see fit, as long as they do not directly harm others or other property. However, there is also no obligation in a free market to purchase products produced from farms, businesses, and industries which are perceived as destructive to the environment. There is nothing preventing the organization of boycotts and peaceful protests. There is nothing standing in the way of purchasing this land for its conservation. There is also nothing that says poor caretakers cannot be shunned completely, if others desire to do so. There is quite a lot of room for deterring industries from environmental destruction just for short term-financial profit, if no one will buy what is produced or if it will cost considerable consumer goodwill in the future. And in extreme cases, independent arbitration may find that some actions on private property are excessively detrimental to the welfare of environmental resources, so as to cause directly harmful effects to other people, and that the perpetrators must be prevented from this. But such a malicious act deserving such an extreme response would certainly be perverse and infrequent, because in general it is direct personal ownership of property which ensures that individual human interests are well in line with wise, considered, and considerate behavior.

In thinking about the ecological impact of business practices, it is important to begin from what is desired rather than means. All too often, concern over environmental problems has stimulated agitation for the centralized ownership, or centralized management of land outside of individual hands, without considering the full implications of that investment of political power — and without realizing that those seemingly direct means will actually be untrustworthy and unlikely to achieve the desired effect of preserving and protecting the worth of environments.

Consider the parallel of art. Relatively few people clamor for central ownership of great art, for its protection. This is not because no one cares about art, quite the opposite. The reason is that there is no need to do so; the worth of most well-known kinds of art is widely recognized and acknowledged, with few exceptions. Just as a private owner of the Mona Lisa would never destroy it, and would be very likely to allow others to experience it as well (probably in exchange for compensation), a private owner of land who recognizes that the environment on his land is valuable in many senses, will be very likely to protect it and care for it well. Increasing awareness of this worth, and increasing the perception of the importance of resources and environmental conservation, helps to bring this about. That is the central task of beneficial environmentalism: education under the assumption that owners are the fitting caretakers of environments, capable of enlightened stewardship due to their own best interests.

The central, ‘communal’ ownership or management of resources and environmentally significant land has tended towards just the opposite from enlightened stewardship. This is especially the case when the avowed ‘community’ is large, and especially when it is structured around government, that is, when it is non-consensual. The larger the group, and the more centralized the political control of the group, the more removed it will be from personal interest, and personal responsibility. Most members of such a group will have no connection to the resources and land, and perhaps no knowledge of it, so that they have not become its caretakers of their own actively interested choice. This explains why small tribal groups which have banded together in consent have with very few counterexamples often managed environments and resources well, usually balancing the need for the use of resources with long-term conservation, both of which are in the personal interests of members of the tribe. Centralized nation-states, however, have a poor historical record. The very worst environmental devastation has been in authoritarian communist states with communal property; the extreme and almost universal pollution, large scale environmental destruction, and widespread disregard for long-term consequences under the centrally-planned economies of the Soviet Union, the eastern European Soviet bloc, and Maoist China are without comparison.

A more moderate example of federal mismanagement of land is the National Forest land in the United States. National Forests are supported by tax money as well as even more considerable visitor fees. As with many public resources, political influence tends to obtain access which is otherwise impossible. This is quite likely the reason why, at the same time that use of this land is limited for most people to charged visitation, subsidies are provided to encourage corporate use of national forests for timber, mining, and grazing. Perhaps these corporations are being responsible, but many feel that they are overusing the land. It might be surprising if they were not. Someone who owns a house and has to live in it is far more likely to maintain it well than someone who can live in a house he does not own, and move from house to house. Certainly, there is no particular interest in managing such land for the future. Not only are the corporations ordered without clear personal ownership and responsibility themselves, there is also no direct link between any individual owners and the land. There is no one to hear complaints except politicians and officials who have mismanaged the land by proxy in the first place, since they lacked a personal interest in it and knowledge of it. If a corporation destroys the land, they do not own it and they do not have to clean it up. If a politician or official entrusts the use of land to a destructive end, or to disastrous administration, it is unlikely they will be personally responsible in the massive, faceless bureaucracy that is the United States government. They will not have to clean it up themselves, and it will not affect them personally. They may never have had an appreciation of the land in question. They may never even look upon the land at all.

Without individually-referenced stewardship based on ownership, there is no personal incentive for the protection or conservation of resources and environments. Private property is no more the enemy of the environment than progress, and it is even more important to the preservation and care of this world. With property comes ownership, and with ownership comes both opportunity for personal gain, and personal responsibility for the future.

6. Monopolies

As long as there is no external interference imposed on the choices involved in the exchanges of a market, everyone in a business is accountable to other people in a way that employed government officials are not. For example, unlike citizens under the one-and-only government, customers can choose to interact with one business over another, and even potentially put businesses out of business, which means that this pressure of competition under normal circumstances makes businesses highly accountable. The exceptions to this occur when either:

• a business receives appreciable support distinct from agreeable exchange in return, support which grants it partial or virtual immunity from this accountability, and resistance to the checks provided by competition, or

• a business has a total enforced monopoly which eliminates competition, or a less extreme, enforced preferential advantage against its competition.

Those exceptions can ensure that businesses fail to be accountable, and flourish despite competition, or because they do not have competition. Therefore the performance of businesses which succeed under such conditions will likely not be serving their customers, employees, partners, and owners as well as some competitors would. And quite clearly, these exceptions are not examples of a voluntary and free economy. A free market does not exist where these exceptions exist, so neither does Promethean capitalism.

Unfortunately, both kinds of interference are quite prevalent within modern ‘capitalism,’ the so-called ‘free markets’ of developed nations.

Subsidies, grants, loans, and bail-outs are all very common examples of unnatural support. So are taxes and regulations, which tend to favor large corporations over the same people and resources split into smaller groups, since large corporations exist as a legal whole, and since they can afford specialists to handle these issues. (However, taxes and regulations weigh down all businesses; it is simply less detracting from a large one than from a small one; these are supports only in relative terms.) Monopolies are ostensibly discouraged and forcibly split, and yet they are encouraged by corporate law and tax laws, which favor size. Today, even the best idea in the most fortunate and capable hands will not necessarily bring competitive success, in a field of large, established corporations — particularly those with political connections.

As a matter of fact, any laws which impact private businesses unevenly, provide an undeserved advantage to some businesses over others. Virtually every law which impacts the creation of something to be exchanged, or impacts those exchanges themselves, will do this. Even under the most limited government, legislation and supplying the function of government will leave a footprint, an influence which will probably produce at least partial monopolistic dominance and accompanying problems.

Even more disconcerting than partial support are the total enforced monopolies supplied by many laws, and by the patronage of businesses by governments. Examples of this include patents, trademarks, and copyrights, which are monopolies over ideas, and the enforced inability to apply ideas and knowledge which one already has. Another example is the defense industry, which has had only a tenuous acquaintance with the principle of independent competition. And of course there are the exclusive contracts made by all levels of government with private businesses selected through a process of political influence (which usually belongs to the larger corporations), contracts which can be so massive that they unbalance whole industries.

There are essentially two understandings of the word monopoly today.

One is not a real monopoly at all. It is a situation in which a business has earned the advantage in an industry or kind of business by competing more successfully than other businesses, offering something more or different, or lowering costs and therefore prices. Such a business may have a large proportion of all the business in their field, but that position has been gained through voluntary exchanges, and it can be challenged any time by the competition of other people, if they are able. This ‘monopoly’ is really just earned success, which in a free market tends to benefit many people, directly and indirectly. To oppose this is to oppose achievement and greatness, at least within a specific economic context. Historically, governmental anti-trust prosecution frequently finds that simple demonstrated superiority within an industry constitutes a monopoly. Possessing a certain percentage of all sales within an industry, even sometimes as little as one or two percent, is an excuse for legal action to ‘break up the monopoly.’ This interference is often instigated and supported by rivals of a successful business. Forcing a business to involuntarily yield what it earns through consensual trade is a tempting means to bypass what would have been required to compete.

On the other hand, a real monopoly occurs when forced control grants a business dominance which cannot be challenged, or an advantage which has nothing to do with achievement and choice. Competition with a monopoly is not allowed, will not be allowed to succeed, or will be artificially difficult. Choice between that monopoly and other options is absent, or artificially discouraged. Unscrupulous practices and exploitation become likely because the exchanges supporting success are no longer voluntary. Without alternatives, there is far less reason to earn profit through valuable and desirable achievements because profit is likely or guaranteed anyway. A monopoly is potentially harmful even to the apparent beneficiaries who have the monopoly, since the deepest personal gain tends to come through achievement, rather than the reward which may follow from achievement. Money is not necessarily the same as profit to a person, after all, especially money which is gained through exploitation.

Monopolies are not natural occurrences in a free market. A monopoly can only happen from force, either physical violence, or intimidation of an implicit threat of violence. Since governments in modern societies have exclusive rights to use socially-acceptable force to oversee exchange, and also make the rules for business in law, government is the only possible cause for the existence of any monopoly which has not been acquired through illegal use of force. The intervention of those in government using the force of law, and the influence of private businessmen in government, in a mixed economy of voluntary and involuntary exchanges, are the causes of monopoly, and all of the worst barriers to individual benefit which are experienced in modern economies.

Given that unnatural monopolies can be very harmful, a final point must be made about government. Government organizations hold monopolies over the making of rules for society in law, and over enforcement. Governments are by far the most powerful monopolies which have ever existed, and they suffer from all the problems of any organization with a monopoly, such as bureaucratic inefficiency due to lack of competition, exploitation, abusive practices, and others besides. The results are inflicted on every citizen; it may be possible sometimes to opt out of a monopolized trade at an acceptable personal cost, but there is no opting out of government. A government breaking up a monopoly amounts to the largest, most complete, and worst monopoly, dedicated to fighting monopolies — gigantic hypocrisy, and a much-advertised distraction from the fact that governments are not necessary to protect us from monopolies. Governments are monopolies, monopolies over the necessary services of protection and arbitration, monopolies which also create more monopolies.

According to Marxist-Leninist doctrine, capitalism will evolve to collapse through the concentration of capital into massive monopolies, in a stage called monopoly capitalism. This concentration of capital certainly does occur, but the ‘capitalism’ of today is not Promethean capitalism. It does not represent capital in an accurately subjective and decentralized understanding of value; it does not allow for free exchange between individual people. The integration of the ultimate monopoly, government, ensures the consolidation of unearned capital in other monopolies. That is the real problem, not capital or capitalism. Otherwise, capital in every sense can be created and exchanged to mutual benefit. In fact, the exceptions to economic freedom which produce monopoly, especially government, would imply at least degrees of fascism, which in economic terms is the systemic interference of government in business, the interference of business in government, and the cooperation of private business and government. True monopolies are really impossible in Promethean capitalism.

7. Economic Fascism

There are two main modern traditions of authoritarian economies. After ignominious experimentation with their severe forms in the twentieth century, today these forms are discredited by their own demonstration. But the full lessons of history remain unlearned.

Government which organizes economic activity based on centralized ownership of property acts as a forced monopoly, since it both engages in production and trade, and makes the rules for production and trade. This tradition is commonly known as socialism, and in its complete form, communism. Basically, this involves the state appropriating the functions of business unto itself, removing the decisions necessary to guide economic action from the control of the individual, and making the individual a direct employee of the state. The state attempts to distribute what is created as evenly as possible, working to limit individual advantage.

Government which does not assume the role of a business directly is capable only of appropriation and redistribution of capital which has already been produced, regulation, and other interference with exchanges of existing capital. This tradition in its more extreme form existed as fascism.

In both cases, distribution of what is created tends to be wasted and hits false barriers all along the way, because there is little personal incentive for efficiency. In both cases, corruption is very likely, because in both cases government is composed of real people whose human nature is no longer an asset, but a problem. In the case of interference with private exchange, officials are likely to interfere for their own profit in business activities of their own, or interfere because they have been paid to intervene on the behalf of certain businessmen, or extort money from businesses in exchange for advantages or being left alone. In the case of government which owns property and engages in exchanges like a business, there is little personal advantage involved with being productive, and little personal accountability for mismanagement and failure. This is why officials charged with the administration of property and goods owned by a government frequently turn to the black market to obtain personal advantage. In both fascism and socialism, competition is lacking which might provide a check against corruption.

Both fascism and socialism focus on the controlled redistribution of what has already been accomplished, rather than more and greater accomplishment. In fact, there is an underlying assumption that what exists and has value is a finite amount with a fixed value. This contradicts any ability of the individual to posit subjective, personal understandings of value.

The difference between fascism and socialism is a fine point in practice. In intent they may differ, but in practice both tend toward consolidation of political power. Socialism typically favors central ownership to a greater degree (in the extreme of communism, all appreciable property is centralized) while fascism emphasizes state control over exchanges more than state control over property itself. With different emphasis, both are based on forced intervention with the individual human acts of creation and voluntary exchange, making creation and exchange involuntary.

The economic fascism which began in the 1920s in Italy under Mussolini’s National Fascists, and in the 1930s in Germany under Hitler’s National Socialists, evolved as a variant of socialism with different goals. The principles of central state authoritarianism and collectivism were the same, in an extreme and at the time more palatable form for being more nationalist, and positioning select industries owned by a select few businessmen to exploit the system in exchange for political support. Likewise, the characteristics of that early fascism in economic terms are still present today, although they are not described as such. The practical characteristics of fascist economics are that:

1) The state is more important than the individual. Forming his own definition of fascism, Mussolini stated, “The Fascist State organizes the nation, but leaves a sufficient margin of liberty to the individual; the latter is deprived of all useless and possibly harmful freedom, but retains what is essential; the deciding power in this question cannot be the individual, but the State alone.” Under fascism, individual freedom is considered dangerous and threatening to the power of the state, more often than it is considered desirable room for individual expression and achievement. Mussolini also said, “Fascism reasserts the rights of the State as expressing the real essence of the individual.” In short, like socialism, fascism is collectivist rather than individualist.

2) Government-business ‘partnerships’ are formed to organize new initiatives designed to improve or expand existing major businesses and industries.

3) Major industries which are deemed essential are planned centrally, with the collusion of both politicians and prominent corporate executives. This central planning seeks market ‘order,’ disdaining the ‘chaos’ which is actually the complexity of independent action within a free market.

4) Mercantilism and protectionism are established to favor major domestic industries at the expense of foreign imports. In a fascist economy, the people who live outside of the borders of the state are considered means for the profit of industries within the state, rather than partners for mutual advantage.

The essential definition of fascism which can be distilled from these characteristics is the co-interference of business in government and government in business, so that the two are inseparable. In fascism there is no major business which is not connected to central planning, and the avowed interests of the state are heavily determined by the wishes of prominent business figures who lead corporations. It is worth noting that economic fascism was more commonly referred to as corporatism by promoters. Today the corporation continues to be the means to consolidate and control modern economies, a container in which individual economic action is more easily managed and integrated with political rule, under the complex systematization of corporate law.

All of the four characteristics of fascism listed above are also present today in the vast majority of modern states, to varying degrees. The differences between the economies of the ‘liberal democracies’ which are professed to have free markets, and the economies of Mussolini’s Italy or Hitler’s Germany, are merely ones of degree and stylistic variation. Just as those tyrants exercised extreme control over personal expression in general, they presided over severe economic control. Just as liberal democratic states allow for more freedom in general, they allow more economic freedom. Yet the telltale marks of fascism are discernable in modern economies, though usually in more moderate forms. This is because the most prevalent economic systems today are just variations on a theme: the economic dominance of the state, control over exchanges within the state and between states, and what has evolved within that system.

“Virtually all of the specific economic policies advocated by the Italian and German fascists of the 1930s have also been adopted in the United States in some form, and continue to be adopted to this day.”

— Thomas J. DiLorenzo

The varied protestors against supposedly disparate concerns such as imperialism, protectionism, monopolies, corporate subsidies, global trade management, price fixing, taxation, tariffs, planned economic development, sanctions, industrial cartels, or corporate irresponsibility should become aware that these are all aspects of economic fascism. These concepts have all been discussed as though they are distinctive in some sense, but they are just different guises of the same sort of economy and the same sort of society: statist, interventionist, compulsive, and collectivist. Do not be distracted by the confusion of sanitized terminology (which has assisted mightily in the extension of the substance of economic fascism and socialism thus far). Instead, we should focus on the foundation of principles and their effects in practice. We then see that economically, fascism and socialism rest on control and dominance, as do the modern states which are wrongly described as supporting free markets and free enterprise.

The dominant economic system today within the political system of “liberal democracy” is a combination of the economic fascist and socialist traditions. If we must classify this system, after carefully examining the facts, we should call it fascism. It is characterized above all by the collusion of governmental and private business, the interests of both indivisibly intertwined in a web of political influence and control — control over competitors, control over personal freedom, control over individual economic identity and the achievement of subjective, personal definitions of profit.

The partial economic interventionism of government under modern liberal democracies has more in common with extreme economic fascism than with the free market of Promethean capitalism. We need to reconsider a worldview that regards America as diametrically opposed to the economy of a highly socialist fascist state, such as China. In reality, the American economy has a great deal in common with the Chinese economy; though it is more free by degrees, it is nonetheless operating by the same principles. Virtually every country is fascist today, differing only in degree and kind of economic freedom which has met with interference from the encroachment of the state and from the commingling of business and government which is inevitable in a statist society. The varying interference of the state in freedom which is not obviously economic is also a matter of degree, rather than delineating entirely different species of societies.

For the most part, property is defined as being private in the “liberal democracies,” although there is some socialistic state ownership. For the most part, that private property is nominally private for the majority of uses, and actually subject to appropriation, control, regulation, and of course fundamental definition by the state. Whenever there is a question of the sovereignty of the individual or the state over anything of value (land, money, time, labor, ideas) the “common good” as defined by the politicians of the state always wins over the private interests of the individual by definition, in even the most liberal “liberal democracy.” As Hitler and Mussolini both found, even the most tyrannical economic supervision and rule can become acceptable to citizens of a democratic state as long as a shell of private property remains in name, and as long as business still makes a profit, though consolidated into strict corporate containers within a tangled web of political control.

“Why need we trouble to socialize banks and factories?”

— Adolf Hitler

Because many wealthy businessmen seek stability so that they can enjoy their success, prosperity within a controlled market may actually serve to perpetuate fascist controls. This was the Chinese rulers’ plan after Tienanmen Square showed them their grip was tenuous; they would buy off the unruly with cell phones and cars produced from the moderate economic freedom of a mere relaxation of the rules. Fascist administrators of markets are not always so cynical, but a tendency is present everywhere to give up on full freedom once personal success has been achieved within the system. The less wealthy are the ones who are often left to demand it. If they are persuaded by those who would maintain power over exchange, lured by the false promises of redistribution, most of the wealthy will be most unlikely to speak up for them. The wealthy are already satisfied — they do not have the same need for a real free market. Consider the example of the past: whenever minor fascism of a more liberal state becomes extreme fascism, major business leaders who speak out against this are a rare prize indeed.

The economies which are commonly regarded as ‘free-market capitalist’ are nothing of the sort. The control of authority has interfered and been involved all along. These economies are the result of private-personal-individual-and-consensual enterprise, ownership, productivity, and economic decisions in an interdependent, interconnected evolution with the centralized political power of government. It is also inaccurate to describe these economies as ‘partially free-market’ because they have evolved under controlled circumstances over many years, to be characterized today by limited independent decision and action. Their character is far from communism, but it is also far from the free market of individuals in Promethean capitalism. The repeated claim that ‘liberal democracies’ represent free-market capitalism is a sham. They have market economies — but not free-market economies. Their politicians often proclaim ‘free trade,’ as long as this only extends to nations, not the exchanges of individual people within them. These states are schizophrenic, caught between the economic rationales of authoritarianism and freedom. Upon realizing this, reasons for the failures of these economies become apparent. The common cause of problems within systems other than Promethean capitalism is the mixing of commerce and force, the co-interference of business and government.

Part of defining Promethean capitalism is defining what it is not. It is not exploitation. It is not invasive control over economic decisions. It is not the heavy cultural influence of centralized economics. It is not forced interference with individual life, which is permissible today most often in the financial sphere. It is not controlled definition or exchange of capital in any sense of the word. Nor does it suffer from the symptoms of control which belong to socioeconomic systems in practice today, and in the past.

8. Symptoms of Controlled Economies

“[T]his loopholes capitalism is not a lasting system. It is a respite. Powerful forces are at work to close these loopholes. From day to day the field in which private enterprise is free to operate is narrowed down.”

— Ludwig von Mises

The fascism which is called ‘capitalism’ in modern ‘liberal democracies’ is more beneficial, more productive, and freer than heavier domination of an economy. But those who defend it do so on the basis that there is no better choice. Promethean capitalism is a real choice which is not a matter of improved variation on the same economic system. The advocates of the lesser fascism in this state capitalism also discount the importance of something which should never be ignored: some control of an economy tends toward greater control, through further aggregation of political power. The proof that their capitalism is not something distinct comes again and again when limited economic control so consistently becomes extreme control, as lesser fascism gradually becomes an unbridled economic fascism akin to that of the Axis powers. The problems symptomatic of a controlled economy remain the same, different only in extent and minor variance. And even as control expands to address them, it extends its own symptoms.

Little can be gained in the long-term from hiding economic realities, which is all that control can do directly within an economy. Centralized organization of production cannot produce more in itself, and it will be removed from the intimate knowledge necessary to set appropriate prices and pay appropriate wages. Official but unrealistic wages or prices, or production quotas, or the support of inefficient businesses, cannot really achieve anything. It may be politically popular to give money and goods away as if they are manna from heaven, but in reality they have a source. Whatever is distributed must have come from somewhere; it must be created to be given away, or it will have to be taken from elsewhere. This is what is happening when the involuntary exchanges of taxation and other mandatory allocation is redistributed in a controlled economy, whether it goes to pay wages which are something other than what work is worth to the employer, or allocates prices differently from what supply would indicate, or pays people to do unnecessary work or to produce goods that no one will buy, or pays them to do nothing at all.

The source of economic productivity is always ultimately individual accomplishment, even within a cooperative group. It is impossible to decree productive economic results, except to limit them as a result of individual reaction to a decree. People will not blindly continue to do what they did before, once central planners build boundaries and change the rules. They respond however they will as individual people. They cannot be herded like sheep as long as individuality remains part of humanity, and so long as their freedom allows it. They will respond unpredictably, and control will have unintended effects.

The incentive to achieve is generally decreased within a fascist economy of any degree. For example, if income taxes increase with greater income, the incentive to make more income is lowered. Starting a business requires special taxes and regulations, often making it not quite worthwhile. Changes in taxes schemes and regulations are an added threat to small enterprises. Established, large businesses have less of a problem weathering such costs and risks. A common thread in controlled economies is that the incentive to express ability by reaching for maximum achievement is lowered considerably, and unevenly. This is especially evident when interference is targeted to achieve specific goals which are deemed beneficial in certain industries. Any regulations by the government designed to affect selective or partial controls on final prices provide less incentive for producers, forcing some investment capital into less affected businesses and industries. In an attempt to achieve the original goal of lower prices or more goods, this process must continue farther and farther afield. Regulation must be spread to the businesses which now benefit from increased capital; the government planners must continually chase capital, or give up the pursuit of specific economic goals through artificial means. If they do not stop and accept failure to control the complexities of human action through rough central decree, the eventual product is the extreme controlled economy of a totalitarian state. In the long term, interference with an economy does not achieve the proposed results; it is only successful at expanding power.

These problems, tied to the accretion of centralized political power as both cause and effect, are bad enough. But they are not the worst part of involvement of government in a controlled economy. They are the just some of the weaker evidence against control, based on a simple and rather naïve view of the process in which officials have benevolent, objective, and merely deluded intentions, and those in business fail to exploit political leverage for their own advantage. In reality, objective separation of business and political interests are impossible in such a system of invasive masterminding. The worst symptoms of economic fascism come from the way that the intertwined coexistence of private interests and public rule breeds abuse of power, bribery, political favors, exploitation, and in general brings out the worst of humanity. And again, there are unintentional effects, which sometimes are even worse than this inevitable corruption.